Investors have watched bond yields in Europe and Japan slide below zero into negative territory, and some have wondered: Could it happen here? Although you can never say never when it comes to markets, I believe the odds are slim, for reasons discussed below.

First, some background: As central banks around the world have struggled to revive inflation and support economic growth, short-term interest rates (“policy rates”) set by the Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank have been at or below zero for quite some time. However, the recent decline in intermediate and long-term bond yields to negative territory has been unprecedented. There are currently about $13.6 trillion in negative-yielding bonds around the world. #munKNEE/Money!

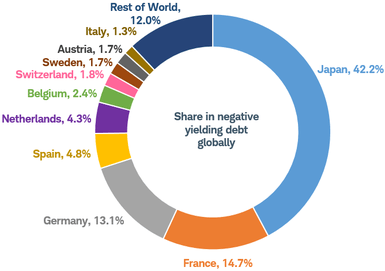

Various countries’ shares of negative-yielding debt

Source: Bloomberg. Monthly data as of 8/1/2019.

However, I believe negative yields are unlikely in the United States. Here are five reasons why:

1. It’s unclear whether the Federal Reserve can push yields into negative territory under the terms of its congressional charter

Former Fed Chair Janet Yellen made this point in 2016 and said that the Fed “would look into it.” To the best of my knowledge, the Fed hasn’t published anything on the topic in the interim, which means it isn’t under active consideration.

- If the Fed were contemplating negative policy rates, there probably would be some articles on the Fed’s website providing evidence why it is a legal and viable option. So far, nothing.

- Moreover, the Fed did not lower the federal funds rate below zero from 2009 to 2015, when growth was softer, deflation was a threat, and other central banks already had gone negative. That suggests some hesitancy to pursue the policy. Even with an inverted yield curve, it would be hard to push bond yields below zero without negative policy rates.

2. The U.S. economy doesn’t really need negative interest rates – at least not now

The purpose behind negative rates is to force money into the economy. If there is a penalty to holding money, then it is assumed the money will end up in the economy instead. Consumers will spend it, companies will invest it, and banks will lend it. Currently, those things are happening in the U.S. with positive interest rates.

Consumers are spending.

- Second-quarter gross domestic product data showed consumer spending rising at a 4.7% pace, and early data for Q3 continue to look healthy.

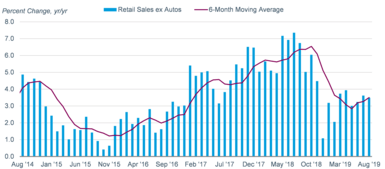

- Retail sales have picked up over the past four months and are growing at a 3.7% year-over-year pace. As consumer spending accounts for 68% of GDP, that’s good enough to keep the economy going, despite sagging future expectations.

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve. Retail Sales and Food Services Excluding Motor Vehicles and Parts Dealers, Percent Change from Year Ago, Monthly, Seasonally Adjusted (RSFSXMV). Monthly data as of August 2019.

Banks are lending.

- The growth rate in bank credit has been running at about a 6% year-over-year pace, which is twice the pace seen at the lows in 2017, and is consistent with 2% to 2.5% GDP growth.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Bank Credit, All Commercial Banks, Percent Change from Year Ago, Weekly, Seasonally Adjusted. Weekly data as of 9/4/2019.

Business investment is slowing, but not because of tight money. The primary cause of the slowdown appears to be uncertainty over trade policy rather than lack of credit availability. In fact, the capital markets are wide open for companies to raise money. Issuance in the corporate bond market has picked up sharply as interest rates have fallen, and even low-rated, junk companies are finding it easy to access capital.

3. The risk of recession is low

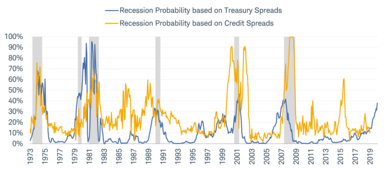

With financing conditions easy, the risk of recession has diminished. There are several models that attempt to rate the probability of recession.

- Those that rely on the yield curve show an increased risk-about 40% while

- those using credit spreads show a low risk – about 10%.

Historically, it has been rare to enter a recession without tight credit conditions.

Source: New York Federal Reserve. Monthly data as of August 2019. Shaded areas indicate past recessions. Recession probabilities predicted using data through August 2020.

4. Deflation is not an imminent threat

Negative interest rates have been used in Europe and Japan, where outright deflation was present. With deflation, negative nominal interest rates can be justified.

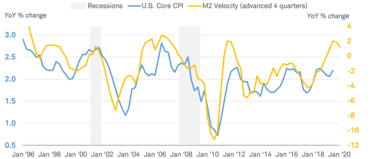

- However, the U.S. isn’t experiencing deflation. In fact, inflation has been edging higher.

- Moreover, the leading indicators of inflation appear to be signaling an increase ahead, not a decline…

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: All Items Less Food and Energy, Percent Change from Year Ago, Quarterly, Not Seasonally Adjusted (CPILFENS) and Velocity of M2 Money Stock, Percent Change from Year Ago, Quarterly, Seasonally Adjusted (M2V). Quarterly data as of 7/1/2019.

Note: M2 is a measure of the money supply that includes cash, checking deposits, and easily convertible near money. M2 is a closely watched as an indicator of money supply and future inflation, and as a target of central bank monetary policy.

5. The track record for negative rates isn’t great

While the European Central Bank (ECB) and Bank of Japan (BOJ) have supported the view that negative rates have been successful in lifting economic growth and inflation, the results have been mixed at best.

- Meanwhile, negative rates can make banks less inclined to lend, limiting economic activity.

- They are also harmful to savers, which may inhibit consumption. The BOJ has had to use “yield curve control” to stabilize yields.

In Europe, one of the drivers behind negative yields is tight fiscal policy, especially in Germany. With a budget surplus, Germany is actually paying down debt, reducing the supply of government bonds to the market. Meanwhile, the ECB is buying government bonds. Consequently, yields are plummeting – especially in Germany, where the continent’s largest economy is slipping into recession. It’s no surprise that departing ECB President Mario Draghi has pleaded for easier fiscal policy to augment monetary policy. The U.S. has a very different set of issues: a large and growing budget deficit, and an increasing supply of Treasuries.

A long way to zero

Negative bond yields can’t be entirely ruled out, but the bar to such a move is high. A steep and prolonged recession, with the prospect of deflation and tight credit conditions, would be pre-conditions in my view – but we haven’t seen that. In the meantime, the Federal Reserve has plenty of room to lower the federal funds rate, currently at 1.75% to 2%, before reaching zero or below.

Implications for investors

We expect the Federal Reserve to lower interest rates to a range of 1.5% to 1.75% over the next few quarters, which should cause the yield curve to steepen to a more normal shape, in which longer-term rates are higher than short-term rates. Barring a recession, 10-year Treasury yields are likely to move back above 2%, although the upside is limited by the low levels of yields in other major markets.

We continue to suggest investors consider:

- using bond ladder and/or barbell strategies to manage the duration in their portfolios…

- reducing exposure to high-yield bonds, which may experience falling prices due to slower corporate profit growth and global growth…[and]

- moving to the higher tiers of credit quality.

munKNEE.com Your Key to Making Money

munKNEE.com Your Key to Making Money